To make Wealthtender free for readers, we earn money from advertisers, including financial professionals and firms that pay to be featured. This creates a conflict of interest when we favor their promotion over others. Read our editorial policy and terms of service to learn more. Wealthtender is not a client of these financial services providers.

➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

Almost all of us aspire to improve our lot in life.

For many of us, this means we’d like to build a nest egg big enough to allow us to stop working at some point before we die.

FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) adherents take it a big step further, trying to reach this “work-optional” status in their 50s, 40s, or even 30s.

One of the biggest hurdles, if you don’t start out wealthy, is that the more you earn, the higher your taxes, even as a fraction of income, due to our tax code’s progressive nature — the more you earn, the higher your tax bracket.

Back in the 1990s, University of Southern California law professor Edward McCaffery reportedly said about building wealth, “Once you’re already rich, it’s simple, it’s easy. It’s just buy, borrow, die.”

What is Buy, Borrow, Die?

In essence, buy, borrow, die is a dead-simple three-step tax-avoidance strategy. This method takes advantage of how the Internal Revenue Code is written to set things up in a way that avoids paying taxes. It is important to note that, per the IRS, tax avoidance is legal, while tax evasion is not.

Here are the three steps involved with a buy, borrow, die strategy:

Step 1: Buy

Since we’re assuming you’re already wealthy, you can afford to buy appreciating assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.).

Step 2: Borrow

As more than one person has observed, banks are eager to lend you money only if you can prove that you don’t need it.

Here, you park your appreciating assets with a financial institution and use those assets to secure a line of credit that’s guaranteed by those assets. This sort of credit line is often called a Security-Backed Line of Credit (SBLOC), and it usually doesn’t require you to make any payments as long as your collateral is large enough relative to your debt.

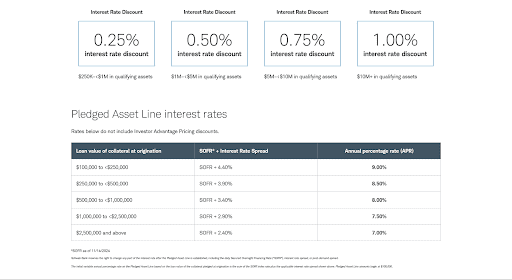

For example, Charles Schwab offers such a line, which they call a Pledged-Asset Line.

As of this writing, their annual interest rate is between 7 percent and 9 percent. However, depending on your collateral and credit line size, you can score an interest rate discount as high as 1 percent. Thus, the real range of interest rates is between 6 percent and 9 percent. The Schwab website states: “Schwab Bank requires that the assets pledged as collateral be held in a separate Pledged Account maintained at Schwab, and that, at all times, the loan value of collateral of the assets held in the Pledged Account(s) be equal to or exceed the greater of (i) the minimum loan value of collateral (currently $100,000) and (ii) the outstanding loans.”

Step 3: Die

Hopefully, you put off this step for many years. The point here is that you never have to do anything more than keep borrowing money to cover your expenses until you die.

Why This Strategy Avoids Taxation

The US doesn’t tax money you borrow, and neglecting sales taxes, it doesn’t tax money you spend.

Further, it doesn’t tax capital gains, i.e., the increase in value of your assets, until you realize those gains by selling assets.

Finally, when you die and leave your assets to your heirs, they enjoy a so-called “basis step-up.” For example, say you buy $5 million worth of stocks and these shares appreciate to $30 million. If you were to sell the shares, you’d owe taxes on the $25 million difference – the capital gains. However, if you die when the shares are worth $30 million and leave these appreciated shares to your kids, the basis for any subsequent sale would be the $30 million they were worth when you died, rather than the $5 million you originally paid.

With the “buy, borrow, die” strategy you never sell assets, so you never pay capital gains taxes. When you die, the basis is stepped up to the assets’ value at the time of your passing. Then, the estate sells enough assets to pay off the money you borrowed over many years and your heirs receive the remaining assets tax-free.

This avoids:

- Federal income tax

- State and local income tax

- Social Security tax

- Medicare tax

- If your estate is smaller than the (generous) exemption, estate taxes; however, as Kyle Newell, Owner of Newell Wealth Management points out, “If one dies with too much wealth (currently over $13,610,000 per the IRS), they should also be concerned with estate taxes eating into their estate in addition to any financing they’d have to pay off at death.”

How This Works Despite Building an Enormous Debt

On the face of it, it may seem that you couldn’t possibly pull this off for a decades-long period because each year your debt increases and accrues increasingly large interest owed.

The trick though is that if your assets appreciate quickly enough, you never owe more than your collateral is worth and the financial institution is happy to keep lending you more.

They know that (a) the collateral makes it exceedingly unlikely that they won’t ultimately get paid back, and (b) the eventual payment will be enormous.

To see this for myself, I ran several scenarios.

For the initial collateral amount I used $5 million – the top of the “High Net Worth” (HNW) range, $10 million – the top of the “Very High Net Worth (VHNW) range, and $30 million – the bottom of the Ultra High Net Worth (UHNW) range.

For each of these, I used three average annual return rates, 7 percent (a plausible return on a balanced portfolio, 10 percent (a reasonable assumption for a stocks-only portfolio), and 15 percent (on the low end of private equity and real estate investments).

For each collateral size and annual return, I calculated for a 35-year period:

- Assets assuming Buy, Borrow, Die (BBD) (in nominal dollars)

- Debt assuming BBD (nominal dollars)

- Net assuming BBD (nominal dollars)

- Assets assuming BBD (inflation-adjusted, or real, dollars)

- Debt assuming BBD (real dollars)

- Net assuming BBD (real dollars)

- Debt load assuming BBD (i.e., debt divided by assets, which must be kept under 100 percent)

- Assets assuming you sell shares to cover expenses (i.e., not BBD) (in nominal dollars)

- Assets assuming not BBD (real dollars)

- The relative effectiveness of not BBD vs. BBD (i.e., the ratio of net assets between the two strategies

For each scenario, I made some simplifying assumptions:

- The appropriate portfolio size at the start

- For BBD, the interest rate from the above Schwab example

- The stated annual investment return, equal for both strategies

- An initial withdrawal rate of 4.6 percent in the non-BBD strategy (this is aggressive, but if you’re willing to cut your budget if the market goes down too far, it’s plausible)

- A total effective tax rate of 28 percent in the non-BBD strategy

- An itemized deduction of $50k for the $5 million non-BBD case, $100k for $10 million, and $200k for $30 million

- An annual budget equal to what the non-BBD case would have after taxes, for both strategies – this was $180k for $5 million, $360k for $10 million, and $1.05 million for $30 million

The Results Are Eye-Opening

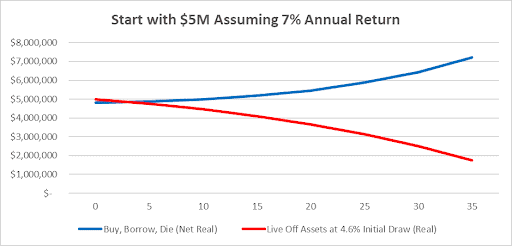

First, we assume a $5 million initial taxable net worth, invested in assets that return an average of 7 percent a year. As seen in the following graph, your net worth would grow to over $7 million over a 35-year period using BBD, whereas it would shrink to less than $2 million in the non-BBD case.

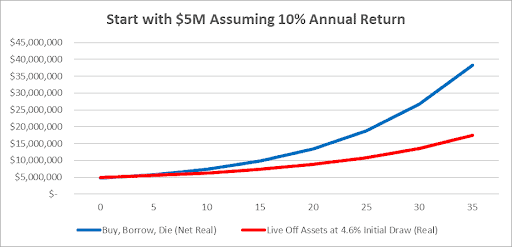

Repeating the above with a 10 percent annual return, your net worth would grow in both cases, but it would reach nearly $40 million (in inflation-adjusted dollars!) using BBD vs. about $17 million with the non-BBD strategy.

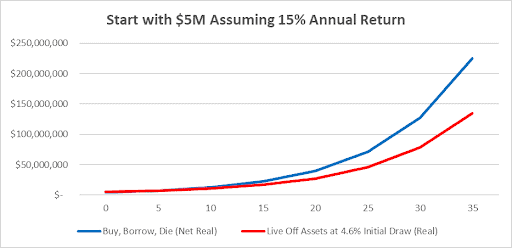

With a 15 percent annual return, the end results are a real-dollars net worth of about $225 million (!) using BBD vs. under $150 million if you go non-BBD.

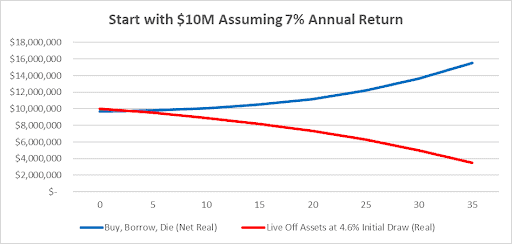

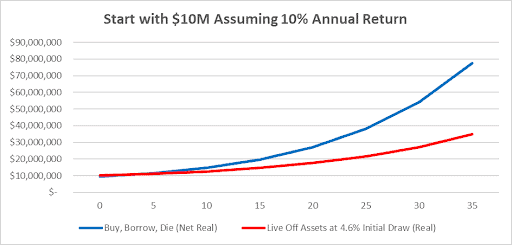

Next, we’ll increase the initial taxable portfolio size to $10 million. Here again, the BBD method increases your net worth, to nearly $16 million with a 7 percent return, vs. shrinking to under $4 million with the non-BBD method.

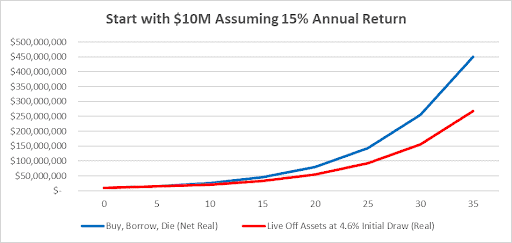

At a 15 percent return, the resulting net worth is $450 million (!!!) with BBD vs. a still incredible but much lower $260 million with non-BBD.

At a 15 percent return, the resulting net worth is $450 million (!!!) with BBD vs. a still incredible but much lower $260 million with non-BBD.

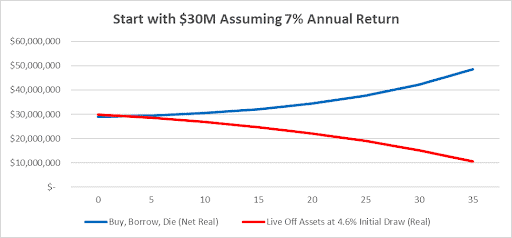

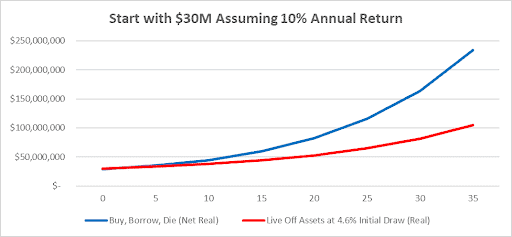

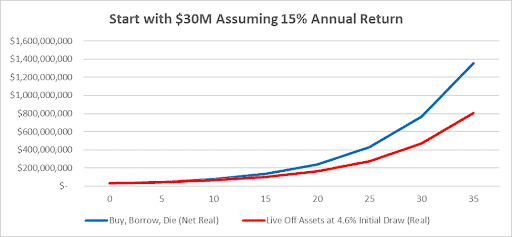

Starting with $30 million, BBD gets you to nearly $50 million with a 7 percent return vs. shrinking to $10 million with non-BBD.

With a 10 percent return, your final BBD net worth is over $230 million vs. just over $100 million with non-BBD.

With a 15 percent return, these numbers increase to nearly $1.4 billion (yes, billion with a “B”) using BBD vs. just over $800 million with non-BBD.

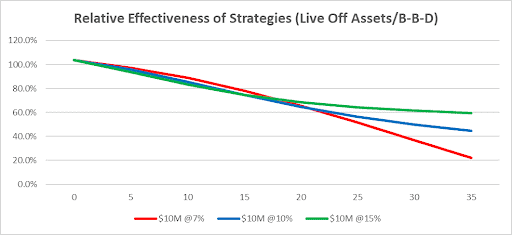

Comparing the final net worth between the two strategies depends strongly (as seen above) on the assumed investment returns, and far less on the starting portfolio size. Thus, we look just at the $10 million initial portfolio case for the three assumed annual returns.

As seen below, with a 7 percent return, BBD outperforms non-BBD nearly 5-fold (non-BBD/BBD is just over 20 percent). With a 10 percent return, that ratio increases to just over 40 percent, while a 15 percent annual return improves the non-BBD to about 60 percent of BBD – i.e., BBD is still far better.

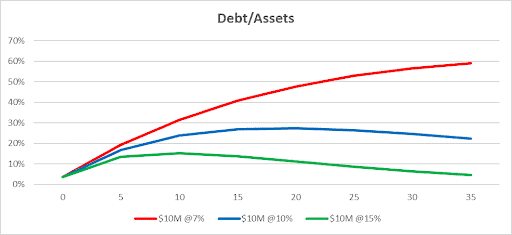

Finally, we can look at the debt load as a fraction of assets over 35 years, assuming you start with $10 million (the results are similar for the $5 million and $30 million starting point cases).

With a 7 percent return, the debt load reaches nearly 60 percent, still far less than the allowed 100 percent.

With a 10 percent return, the debt load reaches a maximum of under 30 percent around year 20 and then starts decreasing, reaching just over 20 percent by year 35.

For the 15 percent return case, the debt load peaks around year 10 at 15 percent, after which it starts decreasing and reaches a mere 5 percent by year 35.

All the above makes it exceedingly clear how important it is for anyone using BBD to invest in a way that maximizes their average return, as long as they don’t take on so much investment risk that their portfolio drops below their debt balance.

Pros, Cons, Risks, and Caveats

The obvious pro is never having to pay taxes despite living a lavish lifestyle and having your net worth grow to an unimaginable size. In the above examples, I used the same budgets for the BBD and non-BBD strategy. However, using the BBD strategy allows you to spend more than what you could in the non-BBD case, while still leaving a larger legacy to your heirs.

Another pro is that assuming your assets are worth far more than your total debt when you pass away, your heirs will be able to use the assets you leave to start their own BBD journey.

The largest con is that you need to already be wealthy to start using this strategy – if you don’t have a large enough portfolio, nobody will let you borrow enough to live on for decades.

Another major con is that you can’t use retirement plans such as IRAs, 401(k), etc. as collateral. If you’re a high earner who used such plans to reduce your taxes owed as you built up your wealth, your taxable portfolio may be too small to make BBD work.

Next, if you have enough to go the BBD route, you take the risk that your collateral may lose enough in value that it no longer exceeds your debt, in which case you’re forced to sell appreciated assets to pay off the debt. Since your assets will likely still be worth far more than they were when you bought them, you’d owe significant capital gains tax.

Between the debt payment and the taxes owed, you might be wiped out, or worse, end up owing more than you can pay off.

Related to this risk, your assets may not be worth much more than your accumulated debt plus interest, in which case your heirs may be left with little or nothing.

Along these lines, Anthony Ferraiolo, Partner Advisor, AdvicePeriod cautions, “The Buy, Borrow, Die method is an interesting one. Clearly, as this analysis shows, it can be a very fruitful method. However, what works in a spreadsheet doesn’t always work in real life. Typically, SBLOCs allow for 50-80% of borrowing power, depending on the underlying assets.

“The two key risks with this strategy (and most strategies) are the following. First, can you withstand the risk/volatility needed to have a very aggressive portfolio? If your portfolio decreased by 30-50%, not out of the realm of possibility if it’s an 80-100 percent stock portfolio, will you have the cash elsewhere to pay down some of the SBLOC debt or will you be forced to sell while prices are low? Not many people have just a $5M – $15M taxable portfolio, but if someone did have this amount, they would probably also have max social security and some IRA distributions.

“Second, a 4 percent withdrawal rate doesn’t account for unexpected life expenses, and the necessary portfolio withdrawal may have to be lower, because portfolio income could likely account for 2 percent of the 4 percent draw, and most people don’t have $0 basis, but they might be able to raise the remaining 2 percent with little to no taxes if done strategically. So, the strategy works much better in theory but has some major risks and unpredictable outcomes you might have to deal with.

“That said, we often evaluate SBLOCs for short to intermediate goals, like buying a home or supporting a lifestyle as you sell another asset in another year. It’s complex and takes a year-by-year analysis. Additionally, we like to keep these loans lower than 30 percent of account values to reduce the probability of a call during a volatile market.”

The main caveat regarding the above analysis is that my simplifying assumptions are exactly that — simplified. Your portfolio will not enjoy a stable annual return of 7 percent, 10 percent, or 15 percent in real life, which increases the above-mentioned risks.

Is a Buy, Borrow, Die Strategy Right for You?

Buy, borrow, die is a fairly straightforward strategy that lets those who are already wealthy (and who have enough of their wealth in taxable accounts) live in luxury while paying zero taxes, and then leave a huge bequest to their heirs.

If you’re in this group and want to implement it, you’d do well to consult with a financial advisor who has expertise and experience in setting up such plans. You also want to consult with an attorney about setting up an estate plan that would accommodate this strategy.

One last thought — this may explain why some billionaire business owners take a $1 salary…

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals. Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.